Screening for Gambling Problems: Have the Conversation

National Problem Gambling Awareness Month

Loreen Rugle, PhD

Assistant Professor, Psychiatry

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Program Director, Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling

March is National Problem Gambling Awareness Month and the theme this year is “Have the Conversation.” NPGA is a grassroots public awareness and outreach campaign created to educate the general public and healthcare professionals about the warning signs of problem gambling and to raise awareness about the help that is available both locally and nationally.

March is a great time to “have the conversation” about the risks of gambling and gambling addiction. The Have the Conversation theme can be utilized in many different settings. Addiction, mental health and primary care providers can screen for gambling problems, which would lead them to “have the conversation” with their clients.

Why Bother? Problem Gambling, Substance Use and Mental Health

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency (SAMHSA) has made health care and health systems integration one of its main priorities to ensure that behavioral health is consistently incorporated within the context of health care delivery systems.

Disordered gambling (DG) is highly associated with substance use disorders (SUD), severe mental illness, depression, domestic violence and suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Afifi et al., 2010; Desai & Potenza, 2009; Kessler et al., 2008; Petry et al., 2005; Grinols, 2004; Ledgerwood & Downey, 2002; Muehlemann et al, 2002; Petry & Kiluk, 2002; Shaffer et al., 1999). A meta-analysis of data from patients in treatment for SUD found that nearly 1/3 of patients across 18 studies were identified as having significant gambling problems (Shaffer et al., 1999). Additionally, the co-occurrence of problem gambling has been associated with indicators of poorer treatment outcome including suicidality, increased service utilization, and use of more intensive services (Desai & Potenza, 2009; Ledgerwood & Downey, 2002). Desai and Potenza (2009) reported that among individuals in treatment for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders, 19% met criteria for problem or disordered gambling, and those with problem or disordered gambling had significantly higher rates of arrest and incarceration, threatening behavior, greater alcohol use severity, higher scores on a measure of depression and more use of outpatient mental health services. More arrests and time in prison have also been reported for cocaine-dependent patients with co-occurring gambling problems (Hall et al., 2000). Among patients in a methadone treatment program, those identified as meeting criteria for problem gambling more frequently had positive toxicology screens for cocaine and were more likely to drop out of treatment early (Ledgerwood & Downey, 2002).

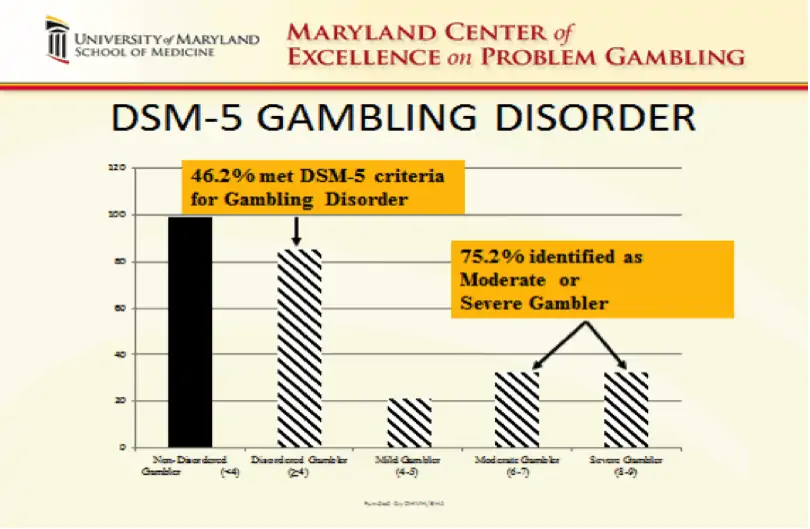

Research at theMaryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling(the Center) has been conducted to inform and support best clinical practices for addressing problem gambling among individuals in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment (Himelhoch et al., 2015a & b). These studies have validated the most effective brief screening tools for evaluation of gambling problems among individuals in SUD treatment and, using DSM5 diagnostic criteria, have reported that more than 46% of individuals in an urban methadone maintenance clinic met the DSM5 criteria for gambling disorder (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percent of clients in SUD treatment meeting DSM5 gambling disorder criteria

Additionally, among those individuals who met diagnostic criteria, over 75% met criteria for a moderate to severe level of gambling disorder, confirming that gambling problems in this population are likely to have a significant negative impact on their lives and SUD recovery. For example, while the average income of this sample was less than $20,000 per year, those identified as having a gambling disorder spent more than an average of $300 per month on lottery tickets alone.

Problem Gambling and Primary Health Care

Disordered gambling has also been linked with adverse health conditions and behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Black et al, 2013; Morasco et al, 2006). Morasco et al. (2006) in their analysis of data from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC)found that persons with DG were more likely to have a range of medical problems, including tachycardia, angina, cirrhosis or other liver disease. Even moderate levels of gambling have been associated with adverse health consequences and unhealthy lifestyle factors. Morasco et al. reported that at-risk gamblers (defined as gambling five or more times in the past 12 months) who they estimate compose 25% of the population, were more likely to have experienced a severe injury in the past year, receive emergency room treatment, have hypertension, be obese, have histories of mood, anxiety, alcohol use and nicotine use disorders.

In a more recent, smaller study, Black et al.found individuals with DG were at higher risk for chronic medical conditions including obesity, heartburn/stomach conditions, headaches, head injury with loss of consciousness, sleep disorders, mood/emotional concerns, and anxiety, tension, or stress. The DG group also was more likely to have poorer health habits. They were more likely to avoid exercise, to drink alcohol while pregnant, smoke greater than or equal to a pack of cigarettes per day, to drink 5 or more servings of caffeine a day, and to watch 20 or more hours of television weekly. Subjects meeting DG criteria in this study were also less likely to have regular dental check-ups and more likely to delay medical care for financial reasons. Additionally, the DG subjects were more likely to have at least one emergency room visit and at least one hospitalization for mental health reasons in the past year.

Individuals with gambling problems have been found to utilize medical and behavioral health services at higher rates (Black et al., 2013; Morasco et al., 2006). Additionally it has been reported that gambling disorder was even more prevalent among nonwhites and thosefrom lower socioeconomic groups. In a study of individuals receiving free or reduced-cost dental care, Morasco & Petry (2006) found rates of problem gambling to be significantly higher than the general population. In their sample, among those receiving disability,26% met criteria for disordered gambling and among those not receiving disability 14% met criteria, based on the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) scores.

Gap Between Research and Clinical Reality for Gambling Disorder Screening

The research as cited above clearly indicates that individuals who are experiencing gambling-related harms in their lives or even those who gamble moderately are likely to experience higher rates of medical and behavioral health problems. However, they are not necessarily likely to seek specific help for gambling problems. For example, in the Himelhoch et al. (2015b) study described above, while almost half of those studied met criteria for gambling disorder, only 6.5% reported ever having talked with a counselor about their gambling. This under-identification and treatment of gambling issues has been found nationally as well. In an analysis of data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, researchers found that of those individuals with a lifetime history of pathological gambling, 49% received treatment for a mental health or substance use disorder, but none received any treatment for gambling problems. Indeed, it is estimated that only between 1 to 3% of individuals nationwide who meet criteria for gambling disorder access gambling specific treatment services (Marotta et al., 2014). While this is in part due to internal factors in individuals with gambling disorder such as desire to resolve problems on their own, shame, guilt, and denial (Pulford et al., 2009), there are also significant provider/institutional factors. Primary among these is the absence of effective screening and intervention strategies for gambling problems in existing health and behavioral health care settings.

Several evidence-based brief screens (2 – 4 items) for problem gambling have been developed and widely disseminated. For example, SAMHSA offers Gambling Problems: An Introduction for Behavioral Health Services Providers, and the The Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling website includes a range of resources in screening, assessment, and treatment. A recent study (Himelhoch et al., 2015a) specifically studied the most common problem gambling screens

- Lie/Bet Questionnaire

- National Opinion Research Center Diagnostic Screen for Gambling Problems-Control,

Lie, Preoccupation Subscale (NODS-CLiP) - National Opinion Research Center Diagnostic Screen for Gambling Problems-Preoccupation, Escape, Return, Chase Subscale (NODS-PERC)

- Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS)

compared to DSM5 diagnostic criteria among individuals in treatment for SUD. The NODS-PERC and CLiP have excellent accuracy at all cut off points, while the BBGS was the only screen that demonstrated satisfactory classification accuracy together with sensitivity, specificity, and hit rate greater than .80. Such research evidence would indicate that these screens should identify rates of individuals with significant gambling problems in treatment populations comparable to those found in research studies. However, clinical reports suggest that when used in actual clinical practice as part of standard intake procedures these screens identify a far smaller percentage of individuals with gambling problems. In Iowa, as part of a performance improvement project, four SUD block grant agencies evaluated the Lie/Bet, NODS-CLiP, and BBGS. This study found that only 1% of clients screened positive using the Lie/Bet and only 3% screened positive using either the NODS-CLiP or BBGS. In Maryland, SUD treatment programs reported into the Statewide Maryland Automated Record Tracking System (SMART) on more than30,000 clients screened on intake for problem gambling utilizing one of the four screens mentioned above or the slightly longer South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS). Comparable to the Iowa data, only 2.5% of these clients screened positive for problem gambling.

While no formal studies have been conducted to help explain the gap between how these screens work in research vs. clinical practice, there have been some differences in the way screening questions have been administered that may be significant. First, in clinical practice, the screening items are generally incorporated into intake forms without any introduction to the area of gambling. However, it is important to introduce and define gambling with concrete examples of the range of activities being assessed (See DG-SBIRT example below). For example, if a client is asked, “Do you gamble?” They may likely say no. However, if this first question is followed by asking the client, “When did you last buy a lottery ticket?” They may well respond by saying, “On my way to this appointment.” It is quite common for people to interpret questions about gambling as only referring to activities like casino gambling and to not consider activities like playing the lottery or bingo. Second, in clinical practice, using just the items included in brief screens, starts off with clinically diagnostic questions representing the most severe level of problem behavior. It may be more useful to begin with less “pathologizing” questions such as asking how often a person has participated in the range of gambling activities described.

| Model for Gambling Disorder SBIRT | ||||||||||

| Client Full SBIRT ID #: | Worker Initials: | Date: | ||||||||

|

Disordered Gambling-SBIRT Pre-screen and Screen |

||||||||||

| For the purpose of these questions, “gambling” means buying lottery tickets, gambling at a casino, playing cards or dice for money, betting on sports games, playing slot machines, video poker or other video gambling, gambling on the internet, betting on horses or dogs, playing bingo or keno. | ||||||||||

| During the past 12 months have you gambled 5 or more times? | Yes | No | ||||||||

| If the answer is yes then proceed to the first three questions: | ||||||||||

| DURING THE PAST 12 MONTHS: | ||||||||||

| 1 | Have you tried to hide how much you have gambled from your family or friends? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 2 | Have you had to ask other people for money to help deal with financial problems that had been caused by gambling? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 3 | Have you ever felt restless, on edge or irritable when trying to stop or cut down on gambling? | Yes | No | |||||||

| If there is a “yes” answer to any of these questions then ask the next 6 questions | ||||||||||

| DURING THE PAST 12 MONTHS: | ||||||||||

| 4 | Have you tried to cut down or stop your gambling? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 5 | Have you increased your bet or how much you would spend, in order to feel the same kind of excitement as before? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 6 | Did you think about gambling even when you were not doing it? (Remembering past gambling experiences, or planning future gambling?) | Yes | No | |||||||

| 7 | Did you go to gamble when you were feeling down, stressed, angry or bored? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 8 | Did you ever try to win back the money that you had recently lost? | Yes | No | |||||||

| 9 | Has your gambling caused problems in your relationships or with work? | Yes | No | |||||||

Total “Yes” Responses

|

||||||||||

The pre-screen and screening approach can allow for brief educational interventions for those who may be at risk (respond yes to gambling 5 or more times a year), including information on correlations between even moderate gambling and increased health and behavioral health risks and guidelines for healthy or low risk gambling. See figure 2 as an example, and for more examples or go to The Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling, Prient Outreach Media. Depending on the number of positive responses to screening items as well as a client’s level of motivation to address gambling issues, more in depth education and/or referral to further assessment and treatment may be offered.

Figure 2: How to Keep Gambling Healthy

In working with SUD and Mental Health (MH) treatment agencies to integrate the topic of gambling and problem gambling (Disorder Gambling Integration – DiGIn – Project),we have realized the importance of moving beyond screening and case identification. The mission of our evidence informed DiGIn Project has become much broader and involves making the impact of gambling on recovery, health and well-being a relevant topic of conversation in SUD and MH programs. This approach recognizes that while disordered gambling can be a co-occurring disorder or sequential addiction for clients receiving SUD and MH treatment, gambling even moderately can also act as a relapse risk factor or contribute to exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. It is therefore important that clinicians have the conversation with clients about whether gambling is supporting or detracting from their MH or SUD recovery and overall health and well-being.

Some tips for starting the conversation about the impact of gambling on recovery

- Ask clients about the first time they gambled, how they learned how to gamble, or the first time they won something.

- Ask clients about what the favorite types of gambling are in their communities.

- Ask clients to describe how they would know if a friend or family member had a gambling problem. What would be the warning signs?

- Ask clients to list the benefits of gambling to their recovery. Ask them to list the possible costs or downside of gambling for their recovery.

Remember, the goal is to keep the conversation going. Having a non-judgmental and non-labeling attitude is key to this approach. The goal is to help clients set their own goals for keeping gambling healthy. If they chose to gamble, it is important that they know how to keep gambling healthy and affordable and that there are resources for help if any warning signs or gambling problems arise.

Loreen Rugle, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland and is currently Program Director of the Maryland Center of Excellence in Problem Gambling. Dr. Rugle brings 30 + years of experience in the treatment, prevention and research of problem gambling to this position. Dr. Rugle has managed problem gambling programs within the Veterans Administration, in the private sector and within state systems. Her previous position was Director of Problem Gambling Services with the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services for the State of Connecticut. She has participated in research on brief screening for gambling problems, problem gambling and co-occurring risk behaviors among adolescents, neuropsychological assessment of pathological gamblers, neuroimaging and genetic studies of problem gambling, psychopharmacological treatment of problem gambling, gambling problems and coping among homeless veterans, trauma history and problem gambling.

Loreen Rugle, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland and is currently Program Director of the Maryland Center of Excellence in Problem Gambling. Dr. Rugle brings 30 + years of experience in the treatment, prevention and research of problem gambling to this position. Dr. Rugle has managed problem gambling programs within the Veterans Administration, in the private sector and within state systems. Her previous position was Director of Problem Gambling Services with the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services for the State of Connecticut. She has participated in research on brief screening for gambling problems, problem gambling and co-occurring risk behaviors among adolescents, neuropsychological assessment of pathological gamblers, neuroimaging and genetic studies of problem gambling, psychopharmacological treatment of problem gambling, gambling problems and coping among homeless veterans, trauma history and problem gambling.