By Arthur Hirsch, The Baltimore Sun, 7:47 p.m. EDT, August 31, 2014.

Bythella V. Johnson lost so much — about $3,000 — on slot machines during a recent trip to Atlantic City with her husband, Gary, to celebrate their 46th wedding anniversary that he threatened to cut the trip short if she didn’t ease up.

The slots are closer than ever now for Johnson, who has pursued the big hit from Las Vegas to Maryland Live, even on the mock slots at Bingo World in Glen Burnie. You’d figure she’d be thrilled about Horseshoe Casino Baltimore and its 2,500 machines opening even closer to her Pikesville home, but she says she’s not. “I don’t care if they open up,” said Johnson, who has won a few jackpots in her time.

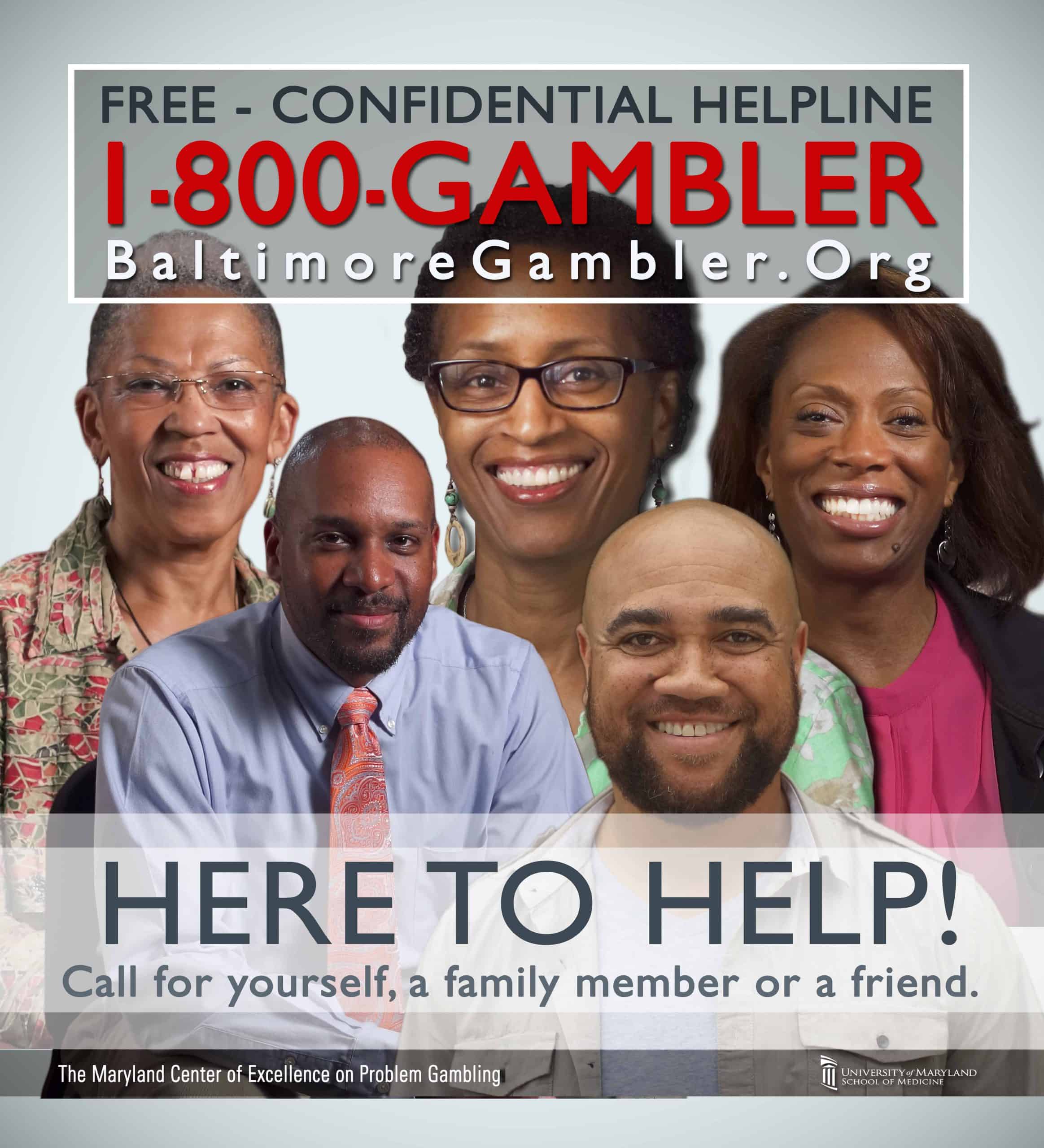

While she can afford to play the slots, she said she’s determined to cut back on gambling, and is lending her voice to a public information campaign by the Maryland Center of Excellence on Problem Gambling linked to the casino’s opening last week. Through a website and advertising on buses, billboards, radio and TV, the campaign pitches restraint to African-Americans, who have been shown in recent research to be more prone than whites to problem gambling.

“Our message is not ‘Don’t gamble,’ because 90 percent of adults in Maryland gamble,” or have in some form, at some point in their lives, said Lori Rugle, director of the program that the state’s casinos are required to pay for under state law. The message — usually with a 24-hour helpline number attached — is to gamble within your means, know the warning signs of a gambling problem and get help if you think you need it.

With the Horseshoe opening, Rugle and others at the problem gambling center are concerned about research that shows African-Americans and people living in low-income neighborhoods were much more likely to develop a gambling problem.

A study released by the center in 2011 estimated that 150,000 Marylanders 18 years old and over — a bit over 3 percent — are problem or pathological gamblers. The figure is based on a national survey conducted in 1998.

The American Gaming Association, which represents casinos, estimates that 1 percent of the adult population has a gambling problem. Industry representatives say they encourage responsible play, that the economic benefits of casinos outweigh risks, and the notion of casinos preying on poor people is overstated.

Visitors to Horseshoe — as at other the state’s other casinos — will find signs and pamphlets around the casino on problem gambling and where to call for help. Jan Jones Blackhurst, spokeswoman for Caesars Entertainment, the lead partner in Horseshoe, said the company trains staff members on how to spot people who may need help and how to intervene if necessary. “We’re about entertainment and having a good time,” she said, “not putting anyone at risk.”

Johnson doesn’t live in a poor neighborhood and is not struggling financially, but the 64-year-old mother, grandmother and great-grandmother has suffered addictions — first drugs, now gambling.

Johnson, who has been drug-free for 26 years, is featured in a video that appears on the website Baltimoregambler.org, sitting on the side steps of her home talking about her struggle. She urges people who are having trouble controlling their gambling to get help before they hit “rock bottom.”

The website defines a problem gambler as someone who gets into financial trouble because of gambling, doesn’t set limits, lies about gambling, loses more than they can afford, and may steal to support their gambling.

Johnson said she hasn’t lost money she and her husband needed to pay bills, but thousands have vanished into slot machines, money she said they might have used for other things.

At her dining room table recently, she displayed a file of bank records showing the $4,120 in checks she wrote in two months last year to Patapsco Bingo as she bet thousands on the Internet “sweepstakes” machines that played like slot machines and paid cash prizes but were ruled illegal. Statements from SunTrust show $800 in ATM withdrawals in three weeks at Bingo World, where an array of electronic bingo machines that also play like slots offer jackpots in the thousands.

“The attraction is, ‘Tonight is my night, I’m going to get it,’” said Johnson, adding that not long ago she was at the bingo hall every day, never walking in with less than $200. “This thing stays in your mind that it’s your night to get it.”

Johnson’s son, known to rap fans as Dboi Da Dome, is also featured in a video on Baltimoregambler.org. He appears with recording artist StarrZ and backup female vocalist Carter in a video shot on a street of boarded-up rowhouses, inside a home and in the recording studio on Harford Road. The video depicts a tale of temptation in a succession of images: Young men shoot dice on the street, Dboi strolls by with cash in hand, a woman in their middle-class home confronts him with a bundle of overdue bills. The refrain urges conservative gambling, not abstinence: “Only spend it if you got it.”

As he grew up in the city, Dboi said, he played a lot of cards and dice and saw the violence that often goes along with them. He’s gambled in the streets and in casinos, won and lost thousands, sold cars and jewelry to pay gambling debts, and ultimately gave it up about three years ago.

“I took a lot of chances being around stuff like that, but when you’re chasing money, you don’t think about that,” Dboi said.